The Tale of a Tropical Terrazzo Driveway as Built in Ecuador

An #oldschool approach to decorative concrete surfaces

UPDATE: 11/09/2017 — added a video to this page which expands on the story below.

We live in Guayaquil and I drive the Ruta a la Costa to get to our jobsites on the coast, in Santa Elena. On route, I pass many little roadside towns that specialize in a trade. For example, people in the pueblo of Atahualpa build doors, millwork, and furniture.

In San Rafael, they sell granito — no, not granite, in the sense we know it as slabs of hard stone, but in its literal meaning of “grains”.

The Sands of San Rafael

Although there is no sign on the road, you will know when you pass San Rafael because the interstate shoulder is lined with lean-tos where young men hawk bags of gravel.

When I first saw it, I thought it was bags of rice!

Some of the young men setup early and stay late, laying on hammocks, wallowing and waiting the long hours under the sun.

Every once in a while, a construction truck stops and buys a load of the gravel to make a particular finishing layer for concrete slabs, including patios, driveways and sidewalks.

It’s common to see the granito finish as you walk about town, and I had been curious about how it was done.

When our contractor, Javier Gonzales, suggested we finish the drive in house with granito, I said yes—mainly to see the process.

It is very similar to terrazzo used in public spaces in the US, but without the final grinding and polishing.

The Local Context

You rarely see a ready-mix truck in Ecuador, especially on a small project. On most jobsites, the most advanced piece of equipment is a gas or electric cement mixer. The mud is carried up 10 stories bucket by bucket.

On our jobsite, all the concrete is mixed the old-fashioned way, in a small heap resembling a bonsai volcano, with sand in a ring and a hole in the center, into which the cement and water are placed, and then the sand is folded and mixed with a shovel.

Because of small batch mixing, slabs go down slowly, concrete lugged in 5-gallon paint buckets, dumped and then spread with a shovel, ironed out by hand with concrete and brick trowels.

Customers in the USA would not accept the final product.

Enter granito that provides a better-looking finish, albeit with a bunch of extra work.

Leveling the Granito Grid

On top of a pretty rough-looking driveway, Javier uses a water level to place lengths of aluminum rail over lumps of mortar, creating a grid. These aluminum rails serve as both float-strips and expansion joints, while creating a decorative pattern—in our case, it’s just rectangles.

Choosing the Aggregate

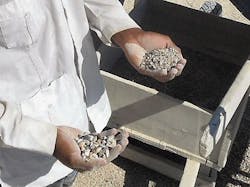

Javier shows me the grade of granito chosen for our job, #3. There are several grades, or gravel sizes available, larger and smaller, with #2 and #3 the most popular for exterior flatwork.

Sometimes different grades are combined alternating for a more interesting pattern, which you can see in the sidewalk combining the two grades of granito to create the contrasting diamonds.

Back at San Rafael

The various grades of granito, from fine sand to course gravel, are separated very much as we do it in the USA, sifted through various sieves, only by hand.

Behind the roadside stands in San Rafael, you can see sand mining in action. The town was built on the banks of a dry riverbed, where locals can extract clean sand and gravel without the problematic sea salt so common to most local sands.

A short sidebar on sand...

If salty seaside sands are used in reinforced concrete, the sodium chloride (NaCl) reduces the structure's durability, with reinforcing steel corroding at much higher rates than normal. This is one reason for the high level of destruction wrought by Ecuador’s 16 April earthquake, the preponderance of cheap, sea sands used in construction – available free.

Salt crystals will also corrode and pit the finish.

So although the sands of San Rafael cost more to buy than simply digging up the seashore for free, but good contractors in any part of the world pay for suitable materials that won’t deteriorate prematurely.

Hence, the folks in San Rafael can make a meager living selling the sands under their homes.

In San Rafael, a young worker, Angel, shows me the process. He has several jigs with two screens. After removing all the large stones by hand, the grains shoveled onto the jig that don’t sift through the first screen, represent the courser aggregate, in this case #3 gravel.

The grains–granito–that fall through the first screen and get caught in the second screen are the #2 gravel. And then on the ground, what’s left is construction sand.

Separation bins for #2 and #3 granito

Two grades of granito

Laying Down the Granito

The granito is mixed with sand and cement to create a heavy aggregate-rich paste. But to make sure the granito—gravel—will adhere to the Portland cement and clean up nicely in the final stages, Javier rinses the granito on a washing jig, bag by bag, before it’s blended into the admixture.

First, a bed of rough mortar is laid over the concrete drive to level the surface to the point right about a centimeter below the screed strips, about 3/8 of an inch.

Then, with a stiff paste made from clean granito, fine sand, and cement, workers place the admixture in alternating, parallel ribbons, allowing them to screed and finish the sections one at a time.

As one finisher works the surface, another comes behind and washes it with clean water to expose the aggregate.

It takes at least two days to finish the process due to the alternating strips. In our case, we finished the first set of strips on Friday, and returned Monday to comfortably lay the second set of parallel ribbons.

Washing Up

After the granito has been placed, the driveway sets over three weeks into a dull, chalky grey. Now it’s time to bring out the shine with a thorough acid wash. Some folks follow-up with a clear polyurethane finish to preserve the wet look, but we won’t.

Javier mixes a witches brew of one-part muriatic acid, one-part bleach, one-part Disma Lavador 501, an Ecuadorian masonry cleaner, and two parts potable water.

He pours this steaming homebrew over the concrete surface and then quickly rinses it off with a power washer, leaving a clean and pleasing exposed aggregate finish.

The process and finish resembles what we call terrazzo, minus the epoxy in the admixture, and the final steps of machine grinding and polishing.

— Fernando Pagés Ruiz is ProTradeCraft's Latin America Editor. He is currently building a business in Ecuador and a house in Mexico. Formerly, he was a builder in the Great Plains and Mountain States. He is author of Building an Affordable House and Affordable Remodel (Taunton Press).

About the Author

Fernando Pagés Ruiz

Fernando Pagés Ruiz is ProTradeCraft's Latin America Editor. He is currently building a business in Ecuador and a house in Mexico. Formerly, he was a builder in the Great Plains and Mountain States. He is author of Building an Affordable House and Affordable Remodel (Taunton Press).