Moving air keeps unwanted heat and moisture out of your roof system

In this episode, we are joined by Sarah Gray, an engineer with RDH Building Science Labs to talk about using simple physics to overcome simple physics. Moisture and heat buildup in roof assemblies are inevitable, predictable, and preventable.

What it is:

roof - ven·ti·la·tion: ro͞of, ro͝of - ven(t) əˈlāSH (ə) n (noun)

"Ventilation is simply moving air from one place to another. In a roof system, it is typically moving the air from the roof itself to the exterior universe."

—Sarah Gray, M.Sc., P.Eng., CAHP

How roof ventilation works:

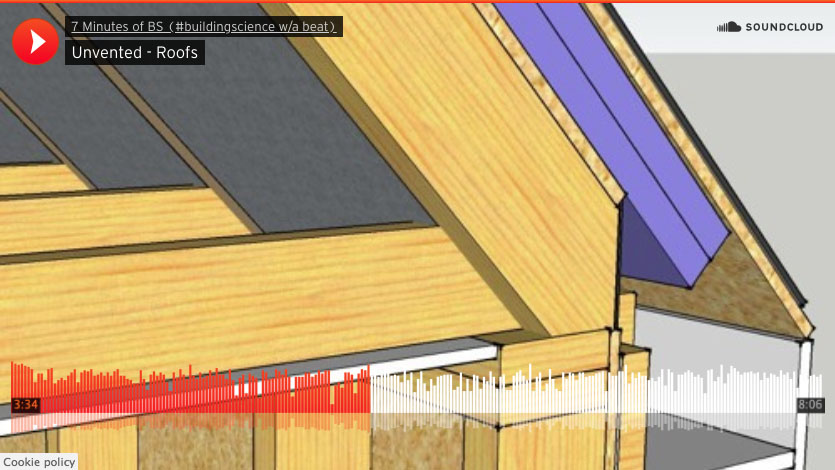

The ventilation air should be located above the insulation, and—usually—below the roof deck.

The main purpose is...

...to keep the air space above the roof insulation more or less at the same temperature as the outside air.

You can vent the attic, the roof, or the roof cladding. The choice depends partly on whether the attic is living space. It also depends on where the insulation is located.

The simplest example is an unoccupied attic with the insulation on the floor. The area above the floor needs to be flushed with outdoor air

If warm air—particularly warm moist air—gets into the attic, that can lead to ice damming...

Which we talked about in a previous episode...

...and also to condensation on the underside of the sloped roof itself.

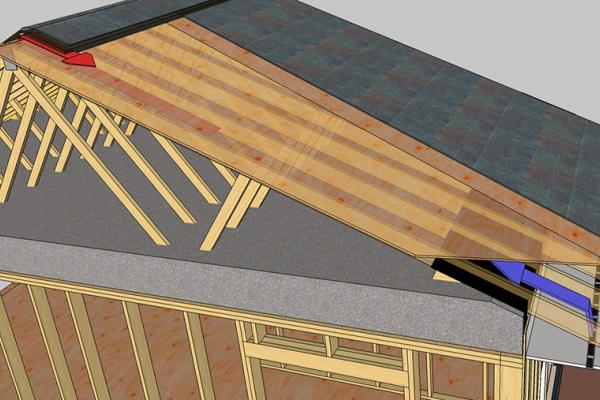

One mechanism driving simple attic ventilation is convection.

As the house loses heat in its top floor into the attic, either by air leakage, or conduction or convection. The top part of the house and the roof will get warm.

As warm air moves to the top of the attic, it pulls cold air behind it.

In a sealed assembly, it turns into a convection loop, it a ventilated assembly, the warm air escapes the top and replacement air is drawn in at the bottom. This constant air movement flushes heat buildup, which can cause ice dams in winter or make your AC work too hard in summer.

We also have some air movement to help clear any condensation or moisture out of the roof assembly.

Why roof ventilation matters:

OK, ice dams, AC, and moisture. Let’s go into a little deeper on why roof ventilation matters.

Roof ventilation matters in cold climates because we want to avoid the risk of both thermal bridging in the roof system which can lead to ice dams, and it’s also important to vent roofs in cold climates to avoid the risk of condensation.

Condensation only matters if the material that the condensation is on, deteriorates, such as wood.

News Flash: Much of what we build roofs out of is wood

Wood rafters

Engineered I-joists

Plywood sheathing

Roof and floor trusses

Other types of wood joists, beams, and purlins.

So if those elements get wet from condensation, it can lead to deterioration over time.

Hot climate roof ventilation is also a response to temperature difference between inside and out, only it is at the other end of the thermometer.

So in hot southern climates, attics can get really warm. And it is not just an issue of stopping condensation. As the roof gets really hot, the materials on that roof can start to deteriorate.

The shingles can curl, crack, dry up, and wither away. They can also go the opposite direction and become saturated…

If you see signs of a lot of wetness, either on the top side of the shingles

Or drips on the ceiling in the winter when it is not raining…

Those may be signs that you don’t have enough ventilation.

How to ventilate your roof right

If you see signs that you don’t have enough insulation, check to make sure that the insulation in the attic is not covering the vents.

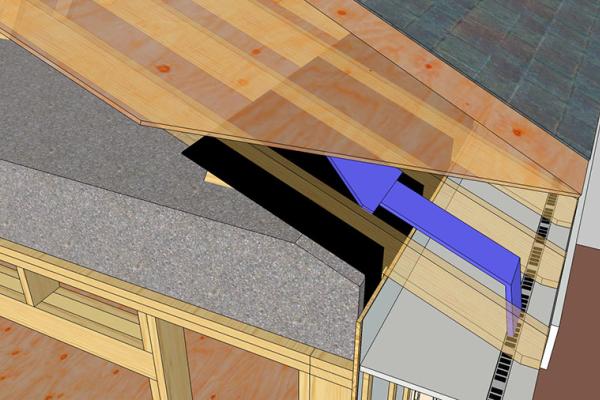

Keeping the path clear is usually accomplished with soffit baffles that bridge the space from soffit to above the insulation. Climb up in the attic,

And pull the insulation back away from the vents so that air can freely move through the vent.

The baffles give structure to the edge of the insulation zone

Sort of like an insulation fence...

Or an insulation dam

Thank you!

To hold that damned insulation in place!

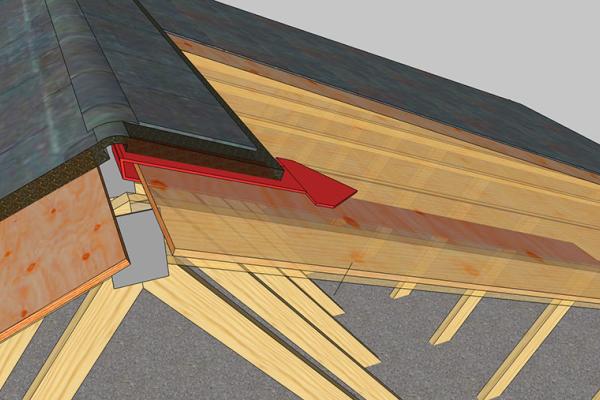

OK, air enters the soffits through louvered vents with an insect screen, it is directed upward past the insulation through a baffle, and it exits at the top most likely through a ridge vent.

In some cases you’ll see a louver at a gable end of a roof.

Gable vents. These are not as effective as ridge vents because they are not as high, but they are better than nothing.

Speaking of which,

Typically you don’t need the metal whirligigs on a roof, unless there is not enough ridge vent.

Whirligigs are basically a last ditch effort to clear the air in an attic because cutting holes in a roof is kind of the opposite of what a roof is supposed to be.

The amount of venting that is required for roofs is typically based on the area of the insulated floor space in the attic.

So you look down from the sky onto the flat face of the attic and you see how much area there is.

According to the 2015 IRC, 1/150th of the attic floor space is how much ventilation you need for intake and exhaust combined. You can cut that in half if you comply with one of the exceptions. One of those exceptions relates to balanced ventilation.

So that you have the same amount of intake as you do outflow at the top.

Sometimes the code will say that you have to have 25 percent of the venting at the eave or at the ridge, or balance it 50/50.

Your mileage may vary, based on your local jurisdiction. Other than that, you are pretty free to achieve it any way you want

It is really just a game of geometry based on the type of roof configuration: a hip roof, a low-slope roof, a gable roof, a steep slope roof, those sorts of things.

For a Gable roof, you would have vents at the soffit, vents at the ridge, and/or vents at the gable.

With a hipped roof, you don’t have those vertical surfaces in the roof, so you’re really just relying on soffit vents and ridge vents.

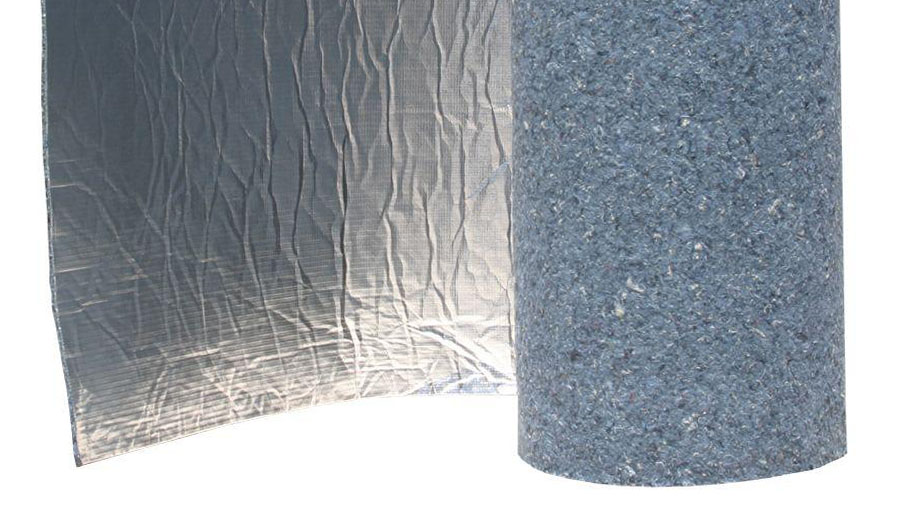

If you have what we call a compact-roof assembly

(a cathedral ceiling,)

There is not a big open attic space to vent the roof.

So you need to squeeze it into each rafter bay to keep the insulation on the inside and the roofing on the outside.

It’s all about a temperature balance and keeping things on an even keel.

That is the last word of today’s Seven Minutes of BS.

Remember, you get paid for what you do and what you know. One thing you can DO to KNOW more is subscribe to this podcast on iTunes, SoundCloud, or The Google. We want to thank RDH Building Science for supplying engineers for the show and for overall adult supervision during the process.

—7 Minutes of BS is a production of the SGC Horizon Media Network. Originally aired April 5 2017

Subscribe: iTunes | Google Play | SoundCloud