Hidden water damage can be a big deal because what you don't see grows

When plumbing lines burst, people notice. Unfortunately, a lot of the moisture damage in houses has nothing to do with bulk water. Instead, moisture trickles into houses through capillarity, air pressure, and diffusion creating hidden moisture damage.

To be sure, bulk water damage is a huge problem, but this article is about the slow, steady, stealthy damage of water sneaking in the back door. And not leaving.

The EPA Water Management Guide is a comprehensive resource covering well over 100 pages. We're going to save you some trouble and consolidate this research into a concise hit list for you to execute in the field.

In Chapter 1, the EPA outlines four key elements of understanding the sneaky side of water.

-

What the symptoms of water damage look like: bugs, mold, rot, rust, efflorescence, spalling, peeling paint, failed floor adhesive, etc.

-

Where hidden water comes from: rain, surface, ground, humidity (inside and outside), plumbing leaks, sewer lines

-

How it travels: capillarity, gravity, surface tension, air currents, diffusion

-

Which parts of the system break most often, based on what has failed in the past: site drainage, gutters, siding, flashing, condensate drainage, humidity controls

This series of articles bundles those thoughts into a practical handbook for keeping houses dry.

Three targets for your moisture design hit list:

1. Control liquid water

Use capillary breaks to prevent water from wicking into the building.

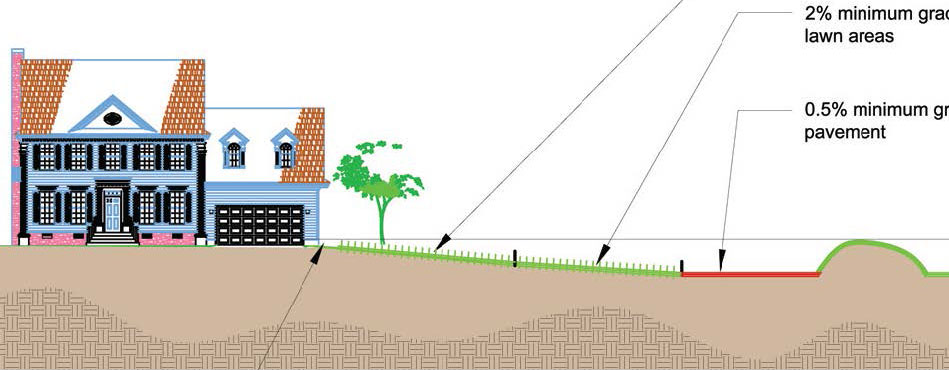

Drain away rainwater, irrigation water, and snowmelt to keep it from leaking into the basement or crawlspace.

Locate the plumbing lines and components where they are easy to inspect and repair (and where leaks will be obvious).

2. Manage condensation

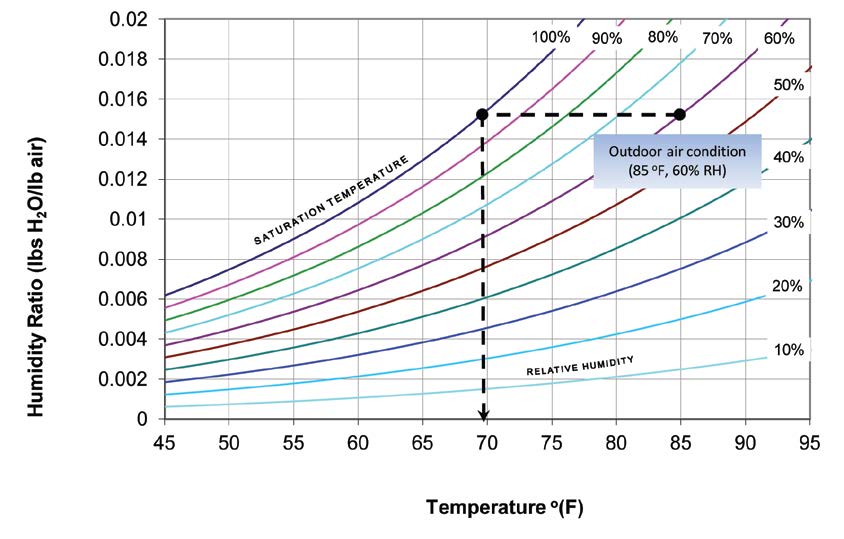

Moist air inside a wall can quickly become a puddle if the temperature drops. Keep (steamy) moist air from creeping into framing cavities.

Use insulation to limit indoor condensation, and make sure condensation can dry out when and where it occurs.

3. Tolerate water in wet rooms

There are two types of wet room to plan for:

1. Rooms that get wet by design, such as kitchens, laundry rooms, and bathrooms.

2. Rooms that get wet by accident, by plumbing leaks, groundwater seepage, roof leaks, and wind-blown rain.

You can't stop the water from coming in, but you can design the room to tolerate and desiccate.

<building code>

2012 IRC:

2012 IECC:

</building code>

Source:

More to explore:

- Building America Solutions Center: Bathroom Exhaust Guide

- Building America Solutions Center: Tub and Shower Guide

- Building Science Corporation: Water-Managed Wall Systems

- Building Science Corporation: Holes and Leaks