Like farm to table for building materials—a tour of Amazon trees and lumber

I was a carpenter in my youth, becoming a home builder when older. Wood, from frame to finish has run through my life and remained a passion: Sawdust, splinters and eyes trained on the pencil marks I trace with my saw. I know wood as a building material. An ingredient of construction.

It’s the trees that I don’t know. I was never curious about them, other than the names, and the working characteristics of a handful of lumber species. Like the difference in the weight of Douglas Fir and the lightness of spruce. I could recognize only a handful of grain patterns, and just barely, such as the differences between red oak, ponderosa pine, paint-grade poplar and walnut. I have known wood the way a short order cook knows hamburger, without knowing anything of cows.

That is, until I took a vacation in the Amazon and witnessed the magnificent arboreal abundance of a tropical rain forest. The impact, visual, auditory and aromatic awakened me to the wonder of trees, although only the hardwood variety. I'll checkout the softwood forests upon my return to the USA.

What dawned on me was the concept of forest to frame. Since my Amazon awakening, every time I see a board, I wonder whence it came from and what it looked like before the chainsaws had their way with it.

My wife Martina swings on a living liana (vine) dangling off a towering tropical Ceibo (Ceiba trichistandra), the king of Amazonian hardwoods, in the province of Tena, Ecuador. The lumber from this substantial hydrophobic beauty is used as durable formwork for concrete—yes, you read it right—as well as shipping pallets and canoes—a crime.

My partner, and best friend, Robert Hampton picks through planks of Amarillo at the lumber yard. As we’ve gotten to know the local woods, the trees and the timbers, the act of building structures with cabinet-grade lumber, forest-to-frame, has changed the nature of wood construction from a commodity-based enterprise to something more akin to cooking, where picking each ingredient is a conscious act, both spiritual and esthetic, as well as practical.

The king of Amazon Hardwoos

El Guayacan (Tabebuia chrysotricha), pictured above, blooms once a year, in a week-long flare-up of blazing yellow blossoms. This slow-growing tropical is the densest and most durable of the Amazonian hardwoods. The sapwood is clear and the heartwood rich as chestnut. With high international demand, the species is now endangered, and it’s harvest strictly controlled. The front door of our cottage was carved form Guayacan. Despite the ban on harvesting it, informal logging and the high prices paid for the lumber conspire to continue its depredation.

Image: http://www.lageoguia.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/P4270231-Large.jpg

The XVII century church pictured above, the Catedral Emperatiz that anchorsthe central plaza of the provincial capital of Santa Elena, Ecuador, was clad in planks of Guayacan, because it remains for centuries immune to insects and weathering.

The dense-as-steel Guayacan has a reddish/black color that makes it prized for construction finishes and furniture. The wood is used for cabinetmaking, furniture, parquet floors, and structural posts. I have a small drawing desk of Guayacan, and it takes two men to lift and move it a few inches. It is heavy.

The treads here look like they need a stringer, but the Guayacan planks are so ridged that when you walk up these steps, the cantilevered treads feel stiff as slabs of concrete underfoot. No steel stiffeners needed.

Not to Be Outdone, Amarillo is plentiful and almost as durable as Guayacan.

The Amarillo (Centrolubium ochroxilmi) tree pictured, and its timber offers many of the aesthetic and structural benefits of the slow-growing Guayacan—and it is not an endangered species. Many roadside cabinet shops will offer you Amarillo saying it's Guayacan. The plentiful Amarillo grows straight up to 25 meters tall, with a heavy, durable pulp that mimics Guayacan in weight and appearance. Once fully dry and stained dark, the trees are timber twins. Also naturally termite resistant, the timbers and planks are popular for structural framing and reusable concrete forms--yes. Abroad it's used for furniture and some of those "live edge" tables so coveted.

It is also popular for charcoal briquets.

Dr. Marcos Sarmiento Ochoa harvests Amarillo on his coffee plantation, and uses it for his endless construction projects in the province of Machala, Ecuador.

The lumber must dry for about three years before use. Dr. Ochoa has a stockpile of Amarillo in a shed bellow his home.

Some hardwoods are incredibly soft.

Almost as ecologically benign as bamboo, Ecuador’s indigenous balsawood remains to be discovered as a green building material in the United States. The trees sprout to 30 meters tall, with trunks as wide as 70 centimeters, ready for harvest in four to seven years. A single kilo of seed from this pod will yield 35,000 Balsa trees (Ocrhoma pyramidale).

The softest of the hardwoods, you’ll be surprised to learn that it belongs to the Mallows family, along with cacao (from which chocolate comes) and the Kola nut (from which CoalCola comes).

Because it grows quickly and tall, balsa trees save fire- or windstorm-ravaged forests. The balsa trees sprout and to shoot up to impressive heights in such a short time that the balsa's wide leaves provide shade to the young seedlings of the slower-growing forest giants.

And you can build with it, more than toy gliders.

You may know balsawood only from the toy gliders you built and flew as a child. You might not recognize it as a construction material used for interior wall panels and floors with characteristics similar to corck.

Light and easy to work with hand tools, balsa is a popular species for erecting partition walls, as pictured here.

Balsawood it also excellent sound isolation, and thermal insulation--although I doubt you'll see racks of it at the lumberyard anytime soon.

But you know teak as an expensive flooring, trim, or furniture wood.

A teak grove in Manabí, Ecuador.You’ll see teak line the perimeter of banana and cacao plantations as a windbreak.

Teak (Tectona grandis) is considered a luxury, cabinet grade hardwood in most of the world. But here remains commonplace. So common that we may use it as siding in the beach cottage we’re building.

Teak groves are grown by speculators to hold large tracts of land in agriculture areas. driving around Ecuador, you’d think these ubiquitous, spindly trees were endemicto South America, but they were brought here from Malaysia.

Nowadays, Ecuador has a primary export business of teak back to Asia. Indians are very fond of the wood as an interior finish.

A teak stairway and planter in Cuenca, Ecuador. Teak offers a brilliant polish when finished, a golden brown, wavy grain that deepens over time, the lumber resists splitting and remains durable enough for marine grade applications.

The brush and jungle vines are also used for construction

I’d seen tangled railings made from the Muyuo shrub (Cordia lutea), but not knowing how it looked alive, I didn’t realize it grew all over our property.

The shrubs don’t look like the source of construction material.

The white little berries, I learned from our contractor, are used as a construction adhesive. And when applied to even the thickest mop of youthful mane, provide a Mohawk worthy of the stiffest shaping gel.

You’ll find the snarled Muyuyo on many exteriors, due to do its durability. A stiff, gnarly branch with a lot of personalities and little to no maintenance required for 25 years or more, it’s popular on railings and garden screens. No need to dry it, harvest in the morning and building your railings in the afternoon.

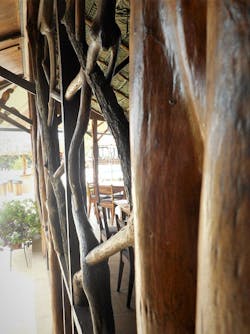

Since I wanted to make the balusters of our cottage out of these tangled branches, our contractor harvested the brush around our property. He also harvested some lianas or jungle vines, the kind my wife is swinging from in the lead photo to this article, to add an artistic flare around otherwise square cut columns.

So many spices of building materials available, the lumber yard seems more like a farmers market for the framer. Or maybe a wine shop, where the lumberman takes you from one varietal to another, declaiming the wonders of each and explaining its terroir, snipping a shaving off with a machete to let you get the nose of it, indulge in the aroma.

Tucuta yura (Guarea sp.) is another hardwood used for exposed, structural framing due to its strength and durability. It dries to a light, reddish color, used for furniture abroad, we use it mostly for posts and beams here at home.

Just as to the wilderness expert there are foods all over the natural landscape, to the builder the tropics offers as many materials as there are trees, shrubs, leaves, and even grasses.

This lonely, straight shoot of Penco (Agave americano) pictured doesn’t look anything like a mainstream building material, but in Ecuador, it is. Like many things in the Andean landscape. Penko, known to the Guarani as “the plant of a million users,” has at least several . A fiber for clothing and rope. A sweetener, related to, but not the same as the agave nectar of natural foods enthusiasts. An Inca inebriant called “guarango”, like the Mexican “pulque”, and the stiff fiber used to give structure to mud plaster and brick.

The living grasses you see sprouting from the walls of this old house are in fact shoots of Penco. The construction style dates to the Cañar and Inca civilizations that settled the area a thousand years ago.

The modern version of this same construction type consists of a Gadua cane (bamboo) structure with thin reads of bamboo as a lath and a stiff blend of mud, donkey shit, and the strands of Penco leaves torn off in ribbons—a little like pealing strips of string cheese, as the fiber that holds the mud together.

At Ingapirca in the Cañar province of Ecuador, you can visit the northernmost outpost of the Inca empire, with its stone temples, and a reproduction of the standard Inca dwelling. The roof is made of Penco thatch. At the eves you can appreciate the detail of the workmanship. The rope used to tie the rafters and fronds of thatch are also peeled off the Penco leaf. Builders in the modern city of Cuenca, Ecuador, still harvest the plant to blend their plasters. Although they don’t use donkey shit anymore. (Material for a later post).

One of the most beautiful woods, used for bold structural members, doors, and exposed rafters, are the timbers of the ultra-hard Seique or Cedrona tornillo (Cedrelinga cateniformis), a member of the cedar family that grows in southern Ecuador and Peru. If you’ve traveled in these countries, no doubt you’ve see it in the most impressive construction of hotels and resorts.

Its flowers are also a common admixture in the psychoactive infusion Ayahuasca. (more material for a future post, eh?)

At the lodge at Papallacta, a small village with volcanic springs in the high Andes of Tena province in Ecuador, the Seique timbers provide structure and drama.

A plain, but elegant Seique door in Cuenca, Ecuador.

Detail of carving on Seique door, the lumber sufficiently dense to work in great detail, with crisp edges and high luster.

Eucalyptus is a common wood in the United States, especially in California, yet I have not seen it used in construction. Along the Andes, this Australian import has found a home, and the local lumber industry exploits it. Considered an excellent structural lumber, due to its strength and rigidity, you’ll find it as both a framing and finish material.

Rustic, eucalyptus treads lead into stone structure.

Naranjo (nothing to do with oranges, except the slight orange tint), is timber used in many rural dwellings, here as a foundation on a bamboo home in the Amazon. It’s also used to provide an eco-natural feel to many trendy constructions, and we’ll be using it our beach development for this reason.

It’s uncivalized twisted and heavily chiseled trunk become symbolic of natural habitat.

Cade palm leaf is the common roof thatch, which comes in bundles, delivered by mule. On the roof, it lasts about five years before needing replacement. The upgrade version of a thatched roof is made of toquilla, the same material of which the weave Panama hats. It lasts about 15 years, and costs about three times as much.

Most homes have Cade roofs.

The picture shows a three-year-old Cade roof on the coast, just south of Salinas, near Anconcito, Ecuador. It’s holding up very well and looks great in this context. I would not recommend it in Virginia, or New York.

Gadua cane, or bamboo, grows in the moist jungle soils to spectacular heights.

A rich architectural heritage exists of bamboo construction, the material is both flexible and strong, allowing the creation of whimsical structures, especially soaring roofs with cambers and curves. Sometime, I'll take you to a nearby factory where they make the bamboo flooors (and cutting boards) green builders drool over.

Most of the Gadua cane structures are roofed with Cade, and you can see the interaction of these sister materials at the eves and overhangs.

The Saman, another Tropical Tyrant

Image at https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/16/Sam%C3%A1n_en_una_quinta_de_Caracas.JPG:

The great Saman (Samanea saman) is one of the forest giants, here pictured in a neighborhood of Caracas, Venezuela. My dining room table, an eight-top, is made from a single slab of it. You can purchase live edge Saman along the road. It’s used mostly for furniture, although beautiful doors are also crafted from single slices.

One if its many uses includes ethanol production, which also seems a crime.

You can find Saman tables on sale along the Coastal Highway in central Ecuador. Some pieces are much wider than the tables shown here.

The Araucaria (Araucarioxylon), here growing in front of the presidential palace in Quito, Ecuador, is one of the oldest species of tree on earth, dating back to the Triassic period (around 150 to 100 million years ago), with some of the oldest fossils dating back 500 million years.

Modern samples can grow to 80 meters tall.

Although the wood from the Araucaria does not have commercial application as a construction material in Ecuador, for many years folks used the petrified remains of these trees, found at the Petrified Forest of Puyango (pictured above), in el Oro province of Ecuador, as building blocks for homes.

Now strictly protected, the Puyango forest has one of the world’s largest collections of petrified wood, comparable to Arizona’s famous petrified national forest. The stone trees found in Puyango average 100 million years of age, and the largest has a trunk 2 meters wide and 15 meters long.

In Chile and Argentina, Araucaria lumber is still exploited for long structural members in construction.

In the 18th century, the trees were harvested for ship masts. Millions of years ago, it also grew in the United States.

— Fernando Pagés Ruiz is ProTradeCraft's Latin America Editor. He is currently building a business in Ecuador and a house in Mexico. Formerly, he was a builder in the Great Plains and mountain states. He is the author of Building an Affordable House and Affordable Remodel (Taunton Press).

About the Author

Fernando Pagés Ruiz

Fernando Pagés Ruiz is ProTradeCraft's Latin America Editor. He is currently building a business in Ecuador and a house in Mexico. Formerly, he was a builder in the Great Plains and Mountain States. He is author of Building an Affordable House and Affordable Remodel (Taunton Press).